The history of diamonds is thousands of years long and filled with desire. Due to its exceptional traits, the Greeks dubbed it “adamant”, “unbreakable”, and “untamed”, the sturdiest precious gem that no other can replace. Even its natural beauty became nothing short of sacred, which is why many were found adorning religious icons as well as fingers, wrists, ears, and necks of ancient rulers eager to demonstrate their power. For millennia, diamonds were literally an embodiment of supreme wealth and stability, but it was until the 19th century that humanity also became fully aware of its application in the fires of industry.

The love and use of diamonds began in India, where most were gathered from streams and rivers. Although the excavated samples were reserved solely for India’s wealthy classes, it also became an exotic merchandise prepared to set sail for medieval Venice markets where they became a fashionable accessory for Europe’s elite. At the beginning of the 18th century, India’s supplies started to diminish, and Brazil emerged as the new greatest source of stunning diamonds, dominating the market for more than 150 years. After Brazil, European explorers discovered great deposits in South Africa, thus broadening the demand and expanding the myth.

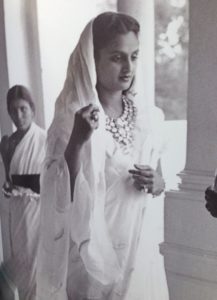

Sita Devi of Baroda wearing her famous diamond necklace.

It is said that in the 1870s, the annual production of rough diamond was somewhat under a million carats, or units of mass. In 1920s, that figure reached three million, while in the 1990s it jumped to more than a 100 million carats. Seems mind-blowing, doesn’t it? Russia and South Africa remain a constant source of high-quality diamonds, but nowadays many other countries, including Botswana, Democratic Republic of Congo, Canada, and Australia, elbowed their way to contribute to those numbers. The interconnected global economy may not be a definition of stability, but diamonds still maintain to flow from mines to cutting centers and ultimately to retailers in spite of such socioeconomic inequalities across the world.

Chemically speaking, a diamond is a metastable allotrope of carbon endowed with superlative physical properties. Due to its atomic structure, it has the highest hardness and thermal conductivity of all materials, making it an excellent component for various engraving, polishing and cutting techniques. It takes a staggering amount of heat and pressure to compress carbon into this face-centered cubic crystal structure, yet we are now able to replicate the conditions similar to the Earth’s mantle where diamonds are naturally made. Due to the rule of scarcity, one would expect that the value of a diamond would have plummeted by now, considering that we can easily make it these days, but that is not the case. And why is that? Adornment. The jewelry industry still holds this precious gemstone in high regard.

Cullinan I, or the Star of Africa, is mounted in the head of the Sovereign’s Sceptre with Cross.

Its splendor has captivated us for centuries. Diamond jewelry was and still is a definition of class and style. We may have gotten a better grasp of diamond’s practical use when scientific knowledge was interwoven with our fascination, but apart from chemists, physicists, geologists, and mineralogists, even your regular Joe wouldn’t miss an opportunity to come in contact with it. Frankly, who wouldn’t?

Humanmade diamonds are best reserved for industrial purposes, while the ones made under the Earth’s surface add something natural and mystical to all those lovely diamond ring designs. Some hitch a ride on an asteroid and fall from the sky like the one found at Popigai crater in Russia, and some even decorate the firmament, as is the case with a white dwarf star near constellation Centaurus described to have a 2,500-mile diamond core that emits a sound of a giant celestial gong. It turns out diamonds are everywhere, and the only question is at which direction do you look to find them.